Mihir Pathak and Srishti Sethi

The giggles and chatter of the children in the classroom could be heard from outside. I reached the class with bowls of different sizes, put the bowls on the table and filled them with different quantities of water. As this setup caught the attention of the children, their voices slowly lowered with excitement.

“What is this sir?”

“Tell me what you think this could be?”

“Sir, is this for a chemistry experiment? Or for some artwork with water colours?”

“Think a little more…”

“Sir, please tell us… at least tell us what this is not?”

“Sir this cannot be something to play with… Sir this is…”

As my students continued with their questions, I began playing music by tapping on the bowls. The children had never seen a jal tarang before!

“So children what did you notice when I played the instrument? What did it sound like?”

The children observed that each bowl with a different level of water in it produced a different sound.

“Can you make a musical instrument using some things around you?”

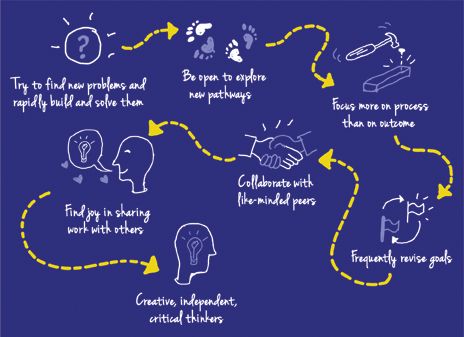

Two days later, my students came with different sound producing objects that they could find at home. One brought a tin, another a clay pot, and some brought bottles of different shapes and sizes with water in them. After they all showcased their musical instruments in class, we read about sound. Playing with materials, discovering new theories behind different phenomena, discussing these with peers to reinforce that knowledge and finding multiple ways to solve a problem – processes like this provide an open environment for children to think and understand concepts and learn skills such as creativity, problem-solving, critical thinking, communication and collaboration. Such a process is known as tinkering.

It is not necessary that such processes should only be limited to concepts related to science. They can be used to teach concepts ranging across the language-mathematics-social science spectrum as well.

“Tell me what is motion? Where can you see motion? What things are in motion?”

“Sir, the fan is moving, the clock too… and outside… the see-saw and swing in the playground are also moving.”

“Great! Let’s use the concept of motion today to make something fun.”

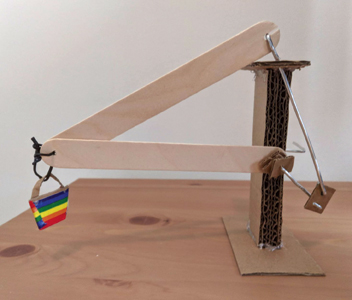

The children got excited and started asking questions like, “Sir, what will you make?” I placed the ‘Vichitra Yantra’ made using a simple crank mechanism in front of them, demonstrating its mechanism, “Tell me, is it in motion or not?”

“Yes, sir”, they cried unanimously.

“Let’s make something like this then. Make groups of five. I have put some things on the table. Use them to make your own version of this toy. Do not copy.”

The work started in full swing. I enjoyed listening to what was going on in each group. I went from group to group observing, giving suggestions and asking questions.

“How would it work if we cut this piece like this?” “What other materials can be used in this?”

“Can we add anything new to this?”

The children were at work for about an hour. Every group then presented its model over the next few classes. We would watch and discuss one project every day. The most important thing in this whole process for me was the increase in the confidence of the children. The children were making enthusiastic presentations in front of their peers, solving problems, working together and learning to learn.

Supporting and designing for tinkering in a classroom setting

In a typical classroom, it is difficult to find time for such activities because of the constant pressure of completing the syllabus. However, it is not impossible to, once in a while, let children have some fun in the classroom. Teachers and children can use free or proxy periods to tinker together. Once children get the environment to explore, they will manage to find the time. So how do you begin tinkering in your classroom? There are a lot of resources (on the internet) from where you can get ideas:

• Tinkering Studio’s project ideas

• Arvind Gupta’s YouTube channel

• Unstructured Studio’s: Repository of Tinkering Activities

• Atal Tinkering Lab’s educational material

From the resources above, here are some examples for tinkering projects and the learning that is associated with them:

• A light story box using cardboard and a torchlight to project shadows onto a wall and narrate stories. Such an activity will introduce children to creative storytelling through animated objects, help them learn how light passes through different materials and forms shadows and connect them with real-life scenarios of light manipulation – such as a projector in a movie theatre.

• A paper circuit using cardboard, aluminium foil, LEDs and batteries to introduce children to electric circuits and their use in real life.

• An ink activity to produce ink using everyday materials like flowers. This could be an interesting activity for children to develop a meaningful connection with their surroundings by better understanding the natural and human-made materials around them and learning how colours are formed.

Choose a simple activity in the beginning. Gradually, you can give more challenging activities to the children. And someday, the children themselves will come up with new activity ideas. The materials used in the activities should be low-cost and easily accessible to children.

Facilitation is an extremely important part of tinkering. To get started with tinkering, first ask the children some questions related to the theme of the activity. Then show an example of that activity using models, videos or photographs. After showing the example, motivate the children to work in groups. If you have a bigger group, you might need the help of another teacher to facilitate. It is very important to ask questions in groups during the facilitation and motivate the children to think about the concept. You can ask questions about the process of the activity, or encourage them to talk about the most challenging part of the project or whether they can use any other material to demonstrate this concept. If the child asks a question, do not give a straight answer. The goal here is to provide children with opportunities to think and communicate. It is also essential to provide feedback to the children when they are doing the activity. Instead of saying “What a beautiful piece of work,” try saying “I liked this particular thing about your model” or “It could have been better if you had….” Motivate children to take feedback from their peers as well.

After all the groups have completed their projects, you can encourage them to document their work and share it with others. You can help clarify the concepts behind the activity and link it to the related subject matter for reflection during the presentations.

Why is tinkering important and its connection with learning in primary grade, especially science?

Tinkering’s fundamental philosophy is based on creating whole and complete individuals who are aware, conscious of their thinking processes and empathize with others.

With my students, I saw an increased interest in science. The natural curiosity to understand how things work with a tinkering activity helps deepen their relationships with the surroundings. They develop an alternative perspective on topics and concepts that we have done an activity around. Yet, one has to be mindful that tinkering without goals and direction will not lead one too far. For subjects like science, inquiry and tinkering must go hand-in-hand with a goal to improve conceptual understanding of a topic and even as children are learning the science behind things, tinkering also helps them learn life skills – patience, persistence, perseverance, communication, critical thinking, etc. Do you need any more impetus to bring tinkering into your classrooms?

Mihir Pathak is a passionate learning facilitator working with children and teachers for the last eight years. He is interested in playful, project based experiential learning and theatre in education. He can be reached at learningwalamihir@gmail.com.

Srishti Sethi is working as a senior developer advocate at the Wikimedia Foundation. She supports the organization’s efforts to engage volunteer developers in Wikimedia software projects. She is also a partner at Unstructured Studio, an organization that designs learning tools and experiences to foster creativity among youth. She can be reached at srishakatux@gmail.com.