Fun as a complement to learning

Malay Dhamelia, Girish Dalvi

We often read articles that argue for making classroom activities fun. The NCERT curriculum encourages visualisations and demonstrations, interactive demos, play activities, and games to complement learning. Using these guidelines, teachers often create their versions of such activities as per the constraints and context of their school. They then put in efforts to plan and coordinate with school authorities, and finally implement these activities in their classrooms. After implementation many are still unable to answer, does fun complement learning? And if it does, in what ways does fun contribute towards student learning?

Several teachers have their own views on this. Proponents of fun believe that where there is fun, there is learning. This group believes that these activities make learning interactive, dynamic, exploratory and most importantly engaging. Students are excited by the thought of doing something other than just sitting in the classroom and listening to the teacher. Such activities are attractive because the engagement is higher and there are multiple opportunities of play in the learning process. A deeper argument is learning should be inherently fun. There should be no separation between learning and fun. Learning in young children is an example to support the argument. Toddlers play and learn many things about the world-motor skills, languages, colours, etc through play. They explore, manipulate, play and understand how the objects and environment work and interact. Since when, the group argues, has fun been separated from learning? Similar to toddlers, students should experience joy from learning and playful activities provide a good way to weave in fun with learning.

The opposing group believes that fun side tracks learning. This criticism comes from the fact that students do have fun in these activities, but that fun is not aligned to the topic being taught. For example, the chapter on “Light, Shadows and Reflection” in the science textbook of class six contains the suggested activity around laws of reflection (Figure 1). This activity is a demonstration of laws of reflection in action. The learning of laws of reflection happens at the end of the activity when the teacher asks questions. Students have fun playing with mirrors. We observe that students merely play with the mirrors and flash the light on each other’s faces and use mirrors to act out different celebrities. Fun and learning both exist in these activities, but they are separate; they emerge through different mechanisms. This type of fun is not anticipated or intended by the curriculum designer; and it is certainly not aligned with the topic. The activity does not become inherently fun, because of which we observe that students merely play with the mirrors. Students create fun themselves if the learning activity is not inherently fun. Because of similar experiences with classroom activities, we think that the activities are ineffective – both in teaching and making learning fun. If we put in efforts to plan, organize and conduct these activities, they have to contribute towards learning and ensure that students have fun.

Arguments from both groups provide value. The proponents of fun argue for introducing joy in learning and making fun and learning seamless. However, the skeptics point towards the design of the activities, their implementation and their effectiveness in both – teaching the content and making it engaging. They ask a fundamental question about how activities can be designed so that they are fun. Fun, through which students learn, fun that is not a distraction but a complement to learning, and lastly, fun that emerges along with learning. They ask how fun can be designed.

Designing for fun is tough. Established games and play designers also struggle to make activities fun. But once the activity is designed, students never cease to play and learn. Let us try to identify what the qualities that make a game fun are and how we can apply them to our classrooms within our context and constraints. Let us re-design the same activity to see how fun can emerge in the same classroom activity around laws of reflection.

Mirror chase – a game around laws of reflection

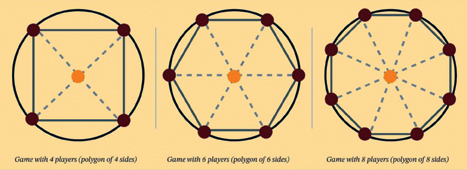

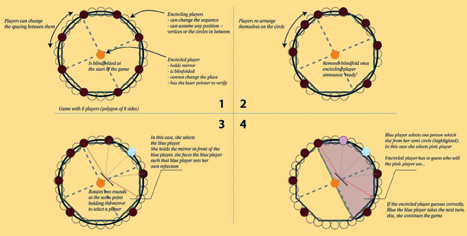

Imagine a group of students standing in a circle as shown in figure 2. Draw a circle using a hexagon or any polygon with an even number of sides. We can use a chalk to draw it on the ground. Students standing on the circle have a low power laser pointer (like the one used for classroom slide presentations). A student stands in the centre of the circle holding a mirror towards the encircling students.

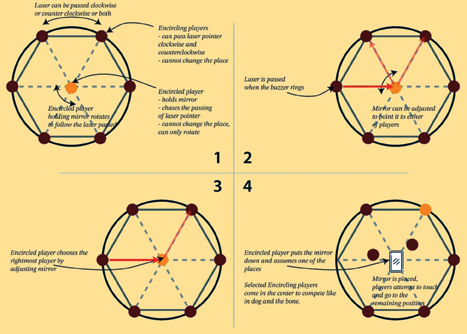

To start the game, students standing in the circle pass the laser pointer clockwise or counter-clockwise; they can choose and change the direction midway (Figure 3). The student in the centre holding the mirror has to chase the passing of the pointer. Once the passing of the laser pointer stops, the student holding the laser pointer has to point the laser to the mirror. The student holding the mirror can adjust the mirror so that the laser is reflected on one of the encircling students. Once the laser pointer touches the other student, the pointing student and the pointed student enter the circle. The player at the centre puts the mirror down and stands in one of the two empty spots on the circle. The two students now in the middle try to touch the mirror first and return to the remaining spot. The student successful in doing so wins that round and the other student (who lost that round) holds the mirror for the next round. Encircling players can come inside the circle before the laser is pointed if they know that the laser will point towards them, thus utilizing their knowledge in subsequent games.

This game is an adaptation of the conventional “Dog and the bone”. However, in Mirror chase, the student in the centre can create competition between players of her choice. The choice and competition allow all the students to learn and internalize that the “angle of incidence is equal to the angle of reflection”. Moreover, the encircling students can choose and change the direction of passing the laser pointer to make it difficult to choose the competitors. Here, fun and learning the law of reflection emerges from the play (it is not imposed or separated). The suggested textbook task-based activity is transformed to an inherently fun game where students are not instructed or asked to perform separate tasks. Instead, a set of rules is given following which students can create both – fun and learning. This re-design of the activity provides several ingredients to create fun in activities.

The first ingredient is autonomy to create fun. Students can choose, create, or change some aspect within the activity. However, this freedom should be coherent to the topic at hand and in conflict with other players’ autonomies. In Mirror chase, the encircling students contest the student’s autonomy in the centre. Each player can change some aspect of the activity. This sense of ability to change some aspects creates fun and engagement. What a student can change has to be coherent with the topic at hand; in our case – laws of reflection.

The second ingredient is uncertainty. It is an essential ingredient to create fun. Players create uncertainty at multiple levels – first, the direction of passing the laser pointer. The player at the centre does not quite know where the laser will stop. She remains engaged in the play because of this uncertainty in passing. The second level of uncertainty is the direction of the mirror chosen by the player at the centre. While she is played by the encircling players, she can make them play by choosing a direction that only she knows. The third level of uncertainty is provided by who touches the mirror first and wins the round among the two players. Thus, if players in an activity can create uncertainty, it becomes fun for all.

The third ingredient is prohibition. It acts silently in the re-designed activity. While players should have the autonomy to change some aspects of the activity, the rules ensure that players do not change anything they please. This restriction should also be coherent to the topic at hand. In Mirror chase, the player at the centre cannot choose anyone. She has to choose the second player using the laws of reflection. This act of choosing internalizes the learning of laws of reflection.

Thus, carefully using the interplay of autonomy, uncertainty and prohibition, we can create inherently fun activities that contribute significantly to learning. These ingredients need to be close to the topic at hand, as much as possible. Utilizing the topic to create these ingredients ensures equal creation of fun and learning. Through such care, we need not “add” or “introduce” fun on top of the activities; students themselves will create fun if the rules have these carefully designed ingredients. Let us apply these ingredients to re-design the same activity (from the textbook) in a different way to see how the interplay happens and how it can generate different types of play.

Axis-Axis (not) – A game around laws of reflection using the same ingredients

Imagine players standing in a circle similar to Mirror chase. However, in Axis-Axis (not), an octagon is drawn on the ground, as shown in the figure below. The encircled player holds a mirror and is blindfolded at the start of the game. Encircling players can arrange themselves in any marked positions on the ground. Once the encircling players are ready, they announce by speaking aloud ‘ready’, and the encircled player opens the blindfold. She is allowed to rotate twice holding the mirror. Then she fixes one of the players and holds the mirror so that one of the encircling players sees herself. The player who sees herself has to challenge the encircled player by speaking out a name from the semi-circle. The encircled player guesses who will see the image of the named person. If the guess is correct, the challenger comes to the centre; however, if the guess is wrong, the player in the centre continues the game.

To decrease the difficulty, we can add guiding lines from the vertices of the octagon to the center. Alternatively, the game becomes less complex if players are not allowed to switch places, but they can move in clockwise or counterclockwise keeping the sequence intact.

Here, the autonomies of the encircling players are created through the choices of positions and the strategies they can create. Encircled players experience autonomy by choosing the player to receive challenges. Encircling players can create uncertainty for the encircled player while she is blindfolded. At the same time, an encircled player can create uncertainty by presenting her choice. The blindfold ensures that encircled players are prohibited from visualizing and the encircling players are prohibited from moving around once they fix positions.

The three ingredients – autonomy, prohibition and uncertainty are amongst many other ingredients of fun. However, these three are essential to develop rules using which students can create fun and learn by themselves. They help create structured interactions where fun and learning are inherent to the activity.

Concluding thoughts

Fun is not an adversary to learning, it just needs to be designed. And designing fun is not resource intensive. As we saw through the re-designed activities, a mere change of rules can create fun. We just need to design the right structures with the ingredients and students will create their own fun and learning. If teachers are the designers of the rules, students are the designers of fun. However, the ingredients have to be as close to the teaching topic as possible. The closer they are, the better the learning and more fun along with it.

Malay Dhamelia is a PhD student at a research group supervised by Prof. Girish Dalvi at IDC School of Design, IIT Bombay. The group works in play, games, player experiences, and design for behaviour change. The group has contributed to play research domains through game design frameworks, created different purposeful games, educational games, play strategies, and design philosophies of play, games and fun. They can be reached at malay.dhamelia@iitb.ac.in and girish.dalvi@iitb.ac.in.